Step-Up: The Most Important Number in Search Fund Investing

How to assess a search fund deal in less than 5 minutes

“Just model the base case to a 30% IRR for investors” - That is the typical answer you will hear when you ask how to determine what terms to offer to investors in your self-funded search deal. It’s a very arbitrary and unsatisfying approach, but the origins are pretty intuitive. Self-funded search is still a new space, so let’s see where else your potential investors can put their money and match or beat it.

With traditional search as an asset class returning about 30% historically and other comparable asset classes like growth equity in a similar ball park, the pragmatic answer is this. Doesn’t matter how you get to your 30%, just make it hit that number and you’re off to the races.

While demand was hot, that approach worked because investors pretty much had to take your terms. In a cooler market, you need to have a better understanding of what your terms mean for the investors to be able to persuade them to invest in your deal.

Typical Self-Funded Search Deal Structures

With the rise in popularity of the self-funded search model (don’t raise money until you have found a deal, use high leverage - typically via SBA 7a loans), the following structure became the standard (with some variation depending on the deal):

75% SBA loan

15% seller note

10% equity (from investors

Investor terms looked something like this:

20% common equity

10% preferred return

Liquidation preference (investors get their money back, before any proceeds get split up among the common shareholders)

Let’s run through an example here and understand what this structure looks like investors for a $3mm deal.

A more Intuitive Approach to Understand Investor Outcomes

There are three common financial metrics to assess the outcome of an investment:

internal rate of return (IRR) - aka what’s the equivalent interest rate

multiple on invested money (MOIC) - aka did the investment double, triple, etc. the initial investment

dollar profit - how much more money did the investors get back than putting it in

Which one matters how much is a philosophical debate in finance circles, but I believe for SMB deals, MOIC matters most and is the most helpful discussion basis between searchers and investors.

Let’s say as an investor you are looking for a 4.5x MOIC in your SMB deal. For reference, most private equity funds are trying to achieve 3.0x MOIC, so 4.5x for SMB feels appropriate give then additional risk in small businesses. By the way, a 4.5x MOIC over 5 years is a 35% IRR, sot there’s your ~30% again.

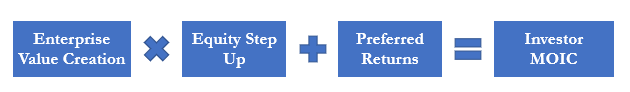

Here’s a great way to break down how that return is generated.

If this seems mathy, don’t worry, it’s very straightforward and will help you talk less numbers with investors in the future.

Enterprise Value Creation1: This is just simply sale price divided by purchase price. You buy a business for $3.00mm, sell it for $4.5mm, your Enterprise Value Creation is 1.5x.

Equity Step Up: Investor common equity ownership divided by cash as a percentage of total purchase price. In the example above, the investors put in $300k (10% of purchase price) and receive 20% of the common equity, the step up is 2.0x

Preferred Returns: Investor receive a liquidation preference that pays them back the initial investment before any proceeds go to the common shareholders, so that’s worth 1.0x MOIC. In self-funded search deals investors typically also get a preferred rate of return. Say it’s 10%. Over 5 years, that’s another 0.5x MOIC.

Using this Approach in Investor Conversations

Unsurprisingly, most investor conversations revolve around the upside of the business and the amount of equity they are getting in the business - Enterprise Value Creation and Step Up.

If you pay a higher multiple or have a slower growing industry, you might need to offer a higher step up - i.e. give up more equity. Vice versa, if you found a great deal, you might get away with a lower step up. In general, the Enterprise Value Creation factor is obviously very subjective, while the Step Up factor is guaranteed. So you need a good story for investors why they should give up equity.

This approach also helps you solve any difference in opinion. Say you are much more bullish on being able to grow the business (Enterprise Value Creation) than the investors. You can offer a higher preferred rate of return to retain as much equity as possible while giving investors the MOIC they are looking for.

Caveats and Edge Cases

Over-equitized deals: With high current interest rates (10%+ SBA loans) and still high seller expectations, deals might need more equity to get done than the typical structure above. The Step-Up requirements make over-equitizing deals painful for searchers. If you need to raise an extra 10% of the purchase price in equity, you now have to give up 40% of the common instead of 20% to achieve the same step up and offer the same returns.

Adjusted Step Up for Value Buys and Over Payments: For deals that are significantly above or below market value, instead of having very high or low Enterprise Value Creations, the better way is to adjust the Step Up.

For example, say a searcher has a business under LOI for $2mm that should really trade for $4mm, and the searcher is offering 15% common equity for 10% of the purchase price ($200k at a 1.5x step up). You’re really putting in $200k into a $4mm business (5% of purchase price) and getting 15% equity, so the adjusted Step Up is 3.0x and you would use the $4mm as the purchase price for the Enterprise Value Creation.

On the flip side, if a searcher has a business under LOI for $6mm and is offering 25% equity for $600k (10% of purchase price - 2.5x step up), but the business actual value is $3mm. You’re actually putting in 20% of the market value ($600k on $3mm) while getting 25% of the common equity, so your adjusted Step Up is 1.25x and you would use the $3mm as the purchase price for Enterprise Value Creation.

Limitations of the approach: There is a major simplifying assumption in the Enterprise Value Creation that the interim cash flows exactly repay the debt, the initial equity investment and the preferred returns. Obviously, that isn’t the case in reality. The winners will generated significantly more cash than that, the losers won’t get there. This is also a very meaningful effect for high multiple businesses >10x. However, for typical search fund deals it’s a helpful back-of-the envelope model.

Conclusion

Once you know the different components of investor returns, you can tailor your pitch to maximize your desired outcome. If you think you have a home run on your hands, offer more preferred return and try to maximize your equity. If you want to be more conservative, offer lower preferred returns but higher equity. If you think you’re paying below market, make sure to outline why that’s the case and that you should get more sweat equity for finding the deal.

There is a significant simplifying assumption here that the cash the business generates over the hold period after taxes pays off the debt and repays the initial equity investment including the preferred return, but there is no additional cash generated. This holds roughly true for businesses bought at 4-5x EBITDA, but the numbers can differ significantly to the upside for very cheap businesses (<3x) and to the downside for expensive ones (>6x).

This is incredibly helpful as I start my journey into ETA without a background in this. As a very hands on learner, I would love to dig into the mechanics of this and experiment. Any chance you have this in spreadsheet form that you could share?

Well said! This article has a great mix of brevity and depth.